Written by Michael Ortiz-Castro, Harvard University

Ferenc Gyorgyey/Stanley Simbonis YSM’57 Research Travel Grant recipient, 2023-2024

Medicine shows were grand spectacles—among some of the first large scale, public, and free theatrical venues in the United States. The spectacles were incredibly popular in the U.S., particularly in the South and the West, from the 1870s to about the 1930s, when they were displaced by films and moving images. These shoes were designed to sell patent medicines—tonics, tinctures, and creams akin to today’s “As Seen on TV” medicines. These medications were popular throughout this era, until increased regulation in the early 20th century led to the development of properly vetted medications. Medicine shows, in their attempts to sell to customers, borrowed theatrical elements from other genres such as vaudeville and, significantly, minstrel shows. While historians of medicine who write on the history of these spectacles have noted the show’s problematic usage of images of Native peoples, not many have talked about the usage of blackface elements.[1] The collections at the Medical Historical Library in the Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library help historians further interrogate the usage of images of the Other in these shows, and, as I argue in my dissertation, help understand how medicine shows “performed” American identity through their linking of race, prosperity, and health.

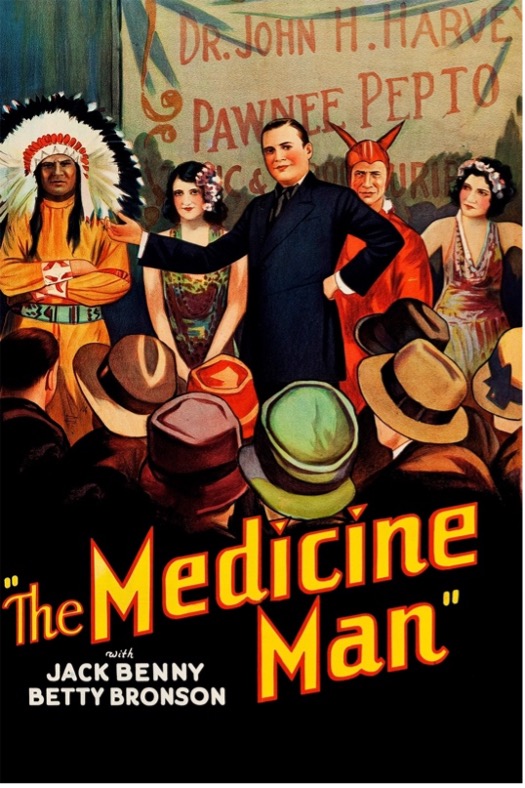

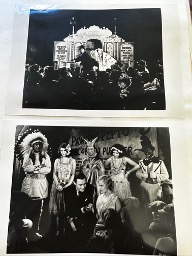

The 1930 film “The Medicine Man” tells the story of Dr. John Harvey, a traveling salesman who lands in a nameless American town and falls in love with young Mamie, who is abused, along with her siblings, by their domineering German father. Harvey’s traveling circus attracts the attention of Young Mamie, and the film details their romance and his rescue of Mamie from her father’s plans to marry her off to a rich older German.[2] [3] The movie’s plot is lifted from the traveling show of the same name, which was used to market Pawnee Pepto—a patent medicine that promised to cure all kinds of ailments in its consumers. While the film spends more time on the romance between Dr. Harvey and young Mamie, an informed viewer will see vestiges of the original source within the film—a short scene of Harvey’s presentation in the town, and other characters’ acknowledgement of the impressive “Indian” traveling with him. Consider the film’s official movie poster, which features Jack Benny in the titular role front and center. He is flanked by a motley crew of characters—two women in Hawaiian inspired costume, a man dressed as the devil, and the “Indian”. The film poster, however, when juxtaposed with a shot of the live medicine show, reveals a critical occlusion: a blackface character, who flanks Dr. Harvey on the stage.

From the scant archival record, it’s hard to say what role these characters played in the medicine show. Scholars who write on medicine shows have claimed that Native characters associated with patent medicines often served as “verification”—as symbols of unvarnished nature that could speak to the efficacy and “healthiness” of the medicine.[4] What role, then, might have the blackface character have played? Historians of the minstrel genre note that blackface characters allowed white Americans to both reinforce their racist perceptions while also allowing a comical outlet for anxieties and fears over difference and equality (given that minstrel shows became incredibly popular following the Civil War).[5] Positioned alongside the Native figure, the audience might have read the blackface character as “verifying” much like the Native chief. But what did this figure verify? Consider the context of the photo of the live show. The shot captures the climax moment—where Dr. Harvey convinces the young protagonist to run away with him. The characters flank him, like ghosts, reminding the viewer of all the medicine has given him: good health, good morality, and good prosperity. The selling point of the patent medicine was not just that it was good for you—but it could deliver proper health, proper morality, and wealth, the hallmarks of the American “good life”.

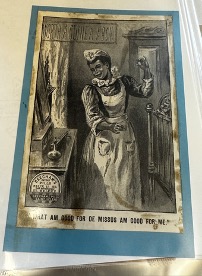

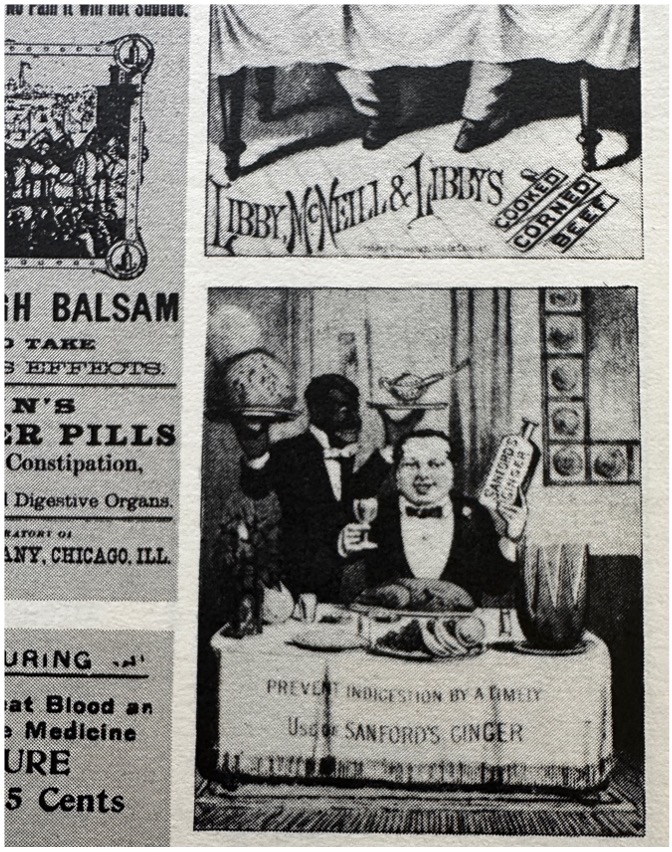

Other ephemera from the Medical Historical Library’s collections allow us to see how blackface/minstrel characters figured into the cultural life of patent medicines. These advertisements for patent medicines used blackface characters to appeal to white customers’ ideas of domesticity and health.

The first ad, for Beecham’s Pills, depicts a black domestic worker, jovially dancing as she holds a small tincture box. The ad’s caption—“What Am Good For De Missus Am Good For Me”—is the ad’s selling point: the black woman’s recognition of the medicine’s value, in her role as the caretaker of the home (the “Mammy” figure), is how the customer comes to understand the value and efficacy of the medicine. Though, as historians have noted, Native peoples were used as symbols of nature that could “verify” the medicine, the deployment of Black bodies as imagery here instead relies on the peculiar domestic relations developed in slavery. That is repeated in the ad on the right, where the prosperous consumer is quite literally “fed” the medicine (here, Sanford’s Ginger) by his stereotypically depicted black servant. The customer’s trust in the medicine comes from the relationship between the white character and his black servant –the servant’s duty and joviality ensure the viewer that the medicine is, indeed, reliable—like the enslaved.

These images suggest that patent medicines, medicine shows, and their associated visual ephemera are best understood not merely as deceptive medical ads, but as cultural forms that, like minstrel shows and vaudeville shows, served to make clear certain cultural ideologies of difference and health operative in late 19th century U.S. Patent medicines were attractive as objects precisely because they spoke to some of the major anxieties at play: economic security, good health, and prosperity to come. Though medicine shows remain undertheorized among historians of medicine, these collections allow us to begin to uncover the genre’s relation to other problematic cultural productions active during the era.

[1] Tomes, Nancy. 2005. “The Great American Medicine Show Revisited.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 79 (4): 627-63. https://doi.org/10.1353/bhm.2005.0173.; Armitage, Kevin C. 2003. “Commercial Indians: Authenticity, Nature, and Industrial Capitalism in Advertising at the Turn of the Twentieth Century.” The Michigan Historical Review 29 (2): 70–95. https://doi.org/10.2307/20174034.; Price, Jason. 2011. “'The Best Remedy Ever Offered to the Public': Representation and Resistance in the American Medicine Show.” Popular Entertainment Studies 2 (2): 21–34.

[2] The Medicine Man, Directed by Scott Pembroke (Tiffany Pictures, 1930).

[3] While the record trail is scant on the medicine show from which the movie derived, historian Irina Podgorny’s “‘Please, Come In’: Being a Charlatan, or the Question of Trustworthy Knowledge” speaks of the show as separate from the film, which implies the existence of the show prior to the movie.

[4] Armitage, “Commercial Indians”.

[5]“Blackface: The Birth of an American Stereotype.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, November 22, 2017. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/blackface-birth-american-stereotype.